Many years ago I was eating dinner in a restaurant in Bucharest when my companions began pointing and whispering excitedly. It turned out that Gheorghe Hagi was eating at a nearby table. I not only didn’t recognize him by sight but I had literally never heard of him despite the fact that he is widely considered to be this country’s greatest football (USA: soccer) player ever.

Likewise, one evening (also many years ago) I was in a suburb of Washington, D.C. visiting a friend when I spied the senior senator from the state of [redacted] walking his dog. I ran into the house, telling everyone I had just seen one of the most influential politicians in the country ambling through the neighborhood but nobody in the house even knew who I was talking about.

So it goes. There are a million celebrities and important people in the various worlds of sports, politicians, music, poetry and painting and any given individual can only be familiar and conversant with some of them. I regularly find myself explaining to Romanians such arcane knowledge as who Gabriel Oprea is and how he managed to become the deputy prime minister of this country even though technically he’s a member of the UNPR and once lost an internal fight for control of the PSD (Prime Minister Victor Ponta’s party).

But everyone, from professors of political science at the university to carrot farmers in rural villages, knows exactly who Mugur Isarescu is.

Since the 1989 Revolution, Romania has seen a lot of politicians come and go. It has had 3 presidents (the fourth one will be elected in November of this year), 11 prime ministers, 185 cabinet ministers and a few thousand different members of parliament. And yet one man, Mugur Isarescu, has been the chief of the central bank (BNR) for 23 of the 24 years since Romania became a democracy.

In 2009, the World Record Academy declared that Isarescu had officially become the longest serving governor of any central bank in history but I wondered if such long tenures were normal (even if not quite as long as Isarescu’s) and so I did some research.

Using Wikipedia, here’s what I found:

The only two countries which come close are Latvia and Bosnia, having had a grand total of two central bank chiefs apiece since 1992 (because different countries became independent at different times, some post-Soviet banks were not created until 1992 so I used that date). Technically Romania has also had two as well because Isarescu stepped down from his BNR duties to be the prime minister in the year 2000.

Latvia however has had two central bank chiefs which split their time evenly, the first (Einars Repse) lasting for an even 10 years and the second (Ilmars Rimsevics) now working on his 13th year.

Bosnia on the other hand is a very unusual case in that their first central bank president (1997-2004) was actually a foreigner, a banker from New Zealand who has no ethnic or linguistic ties to Bosnia but was given the job because Bosnia was essentially an EU colony for many years (with the head of the government being an EU official as well). Since 2005 however, Bosnia has had a local man in charge of their central bank.

So yes, Romania is unusual and very unique in having not the longest-serving governor of a central bank but one who has been in office more than twice as long as the second-place runner-up.

Known Secrets

Isarescu’s term as prime minister is common knowledge of course, as is the fact that he unsuccessfully ran for president in the 2000 elections (coming in fourth place behind Iliescu, Corneliu Vadim Tudor and Teodor Stolojan).

It’s also a fairly open secret that he’s a member of the elite Club of Rome and the even more elite and shadowy organization called the Trilateral Commission.

Ask any Romanian about Isarescu and they’ll generally tell you that he’s been the savior of Romania, protecting this country from the problems that plagued its poorer EU neighbor (Bulgaria) and in general using his intelligence to keep the economy on track. Whatever financial and economic success Romania has had is due to Isarescu’s steady hand on the tiller while whatever financial problems that Romania has suffered was due to the failings of corrupt and stupid politicians.

In English we call that “heads I win, tails you lose” and yet Isarescu has managed to pull off the amazing feat of universally being respected and admired in a country that regularly chews up its leaders in a circular cross-fire of bitter acrimony and reciprocal accusations. Aside from a few deep and dark conspiracy websites implicating Isarescu in a tangled web of shadowy Jewish bankers and complicated Masonic plots, Isarescu is widely lauded by politicians and common citizens from all political parties and all walks of life.

How did Isarescu manage to remain bulletproof all these years?

The ballad of Ion Stan

Back in March of 2012, I wrote an article entitled Economic Assassins which dealt with a statement by a PSD member of parliament named Ion Stan in which he accused the Romanian government (and specifically the central bank) of falsifying economic data in order to deliberately put Romania further into debt (especially to the IMF).

I later did some investigation into these claims for my piece Was Ion Stan Right? and concluded that it seemed like he was far off the mark. It would be pretty hard to hide 20% of a country’s economic production (GDP).

Ion Stan has since faded away and is now under investigation for influence trafficking. Even before that, his star was falling in the PSD as he was given no plum assignments when his party boss (Victor Ponta) became the prime minister.

All that being said, I spent most of yesterday looking through economic data to try to see if there was anything mysterious going on. We all know Isarescu has been (de facto) in charge of this country’s economy since day one and that can only be because it is of benefit to someone.

Is it a case of Isarescu being brilliant or was Ion Stan right when he accused Isarescu of manipulating Romania into debt for a nefarious purpose?

Fifty flavors of debt

The problem with looking into sovereign debt is that it is nothing like personal debt. If I owe the bank a thousand euros then once I pay it back (with interest, of course) I can say that I am no longer in debt.

A country, however, is always in debt. Norway, a tiny country (5 million people) with enormous petroleum reserves (the profits of which go into a government fund called the “Oljefondet” and are used for social programs) and the third-highest GDP per capita in the world, also has debt. In fact, according to the IMF, Norway’s total gross external debt position is 718 billion dollars. How can this be?

Some of it is trade imbalance, in which Norway sells only a limited number of products (petroleum and fish) but has to import all the rest (food and electronics). Some of this import-export is done for “cash” but some of it is done via credit, which gets listed as debt. If I have a thousand dollars in the bank but owe my credit card company 50 dollars then I’m still carrying 50 dollars of debt.

Secondly, all governments sell bonds (or bills or notes), effectively a piece of paper that says “if you lend me a dollar today I’ll pay it back in a year with a little interest tacked on”. Everyone from corporations to pension funds to an ordinary person off the street can buy these bonds (which go to finance government expenditures) and so these too are listed on the balance sheet as debt.

And third, the central bank (in this case, of Norway) lends money to other banks, which is where all those other banks get their money. The commercial banks need to pay back the central bank and until they do, this is also listed on the balance sheet as debt. Even in a profitable economy such as in Norway, the central bank is always going to be lending money to banks which, until it is repaid, is listed as debt.

If a country as obviously as wealthy as Norway has 718 billion dollars of debt, how can you even begin to understand Romania’s debt position?

Making it even more mysterious, other wealthy nations such as Germany (5.5 trillion) and Britain (9.3 trillion) have far more debt than does Romania (134 billion). If I owed the bank 20 thousand dollars and my neighbor owed them just a thousand, wouldn’t you think that my neighbor was in the better financial position? Why does Norway, with a smaller population (5 million versus 20 million) and a higher debt (718 billion vs 134 billion) have such a prosperous economy compared to Romania?

A lot of economists like to simplify things with an equation that measures external debt as a percentage of GDP (Romanian: PIB). If you make $100 in a year and owe the bank $50 then your debt ratio is 50% of GDP. But if my neighbor makes $1000 in a year but owes the bank $50 then his debt ratio is 5% of GDP. We both owe the same amount ($50) but I owe more, relatively speaking, because my debt ratio is higher.

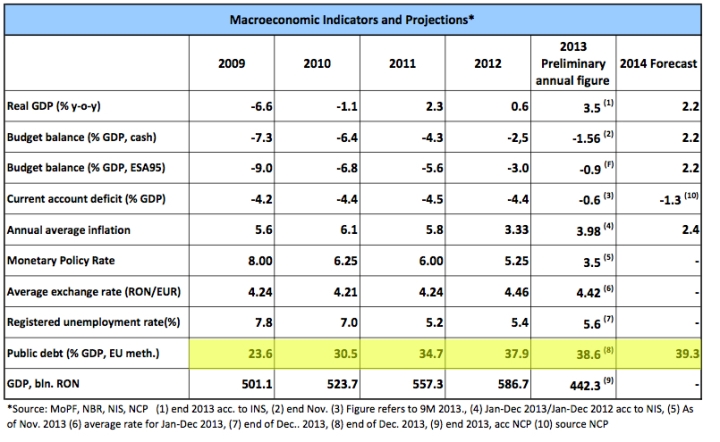

I went over to the Romanian Ministry of Finance and got their latest statistics and highlighted the relevant row for you:

You can see there that in 2009 Romania’s total external debt was 23.6% of its total income (GDP) and it has been going up ever since, projected to be close to 40% this year. Effectively this means that for every $100 that Romania makes, it owes $40 of that to someone else to pay back a debt.

But looking at Norway, you can see that its public debt ratio was 30.3% in 2012 (the latest figures that I could find). That means that while Norway borrowed more money than Romania, its economy makes more money and so it owes a smaller percentage of that to external creditors.

Unfortunately though, even this debt ratio formula isn’t as clear as it should be. Germany’s debt ratio is 83%, Britain’s is around 75% and the United States is at or about 100%. How is it that they are far wealthier nations than Romania is? After all, if I were making $100 a month but had to pay $83 to the bank, I’d be in desperate straits with my paltry $17 left over while my neighbor, who also makes $100 a month, gets to keep $60 (paying just $40).

So we can see that a country like Norway, which has far more debt per capita (718 billion dollars / 5 million citizens = $143600 per person) than Romania (134 billion dollars / 20 million citizens = $6700) and a nearly equivalent public debt ratio (30.3% in Norway vs. 37.9% in Romania for 2012) somehow equates to a GDP per capita of $53000 in Norway but only $13000 in Romania. Norwegians are wealthy and doing well while Romania is one of the poorest countries in Europe.

Therefore you can see that very little is what it seems when it comes to sovereign debt.

Loan Sharks

While just about every country (with a few exceptions) has a central bank that loans money to commercial banks and just about every country (again, with a few notable exceptions) sells sovereign bonds (which function as debt), not every country is indebted in the same way.

There are, effectively, two international banks known as the IMF (Romanian: FMI) and the World Bank (Romanian: Banca Mondiala) and not every country owes money to these two institutions. While the IMF provides “technical assistance” to Britain, Germany and Norway, none of these countries owes a single penny to the IMF to pay back any loans.

Note: every member of the IMF (and World Bank) is a kind of “stockholder” and is required to pay a certain amount of money into the bank (plus fees) but this is offset by payments (plus interest charges) that are paid by debtor nations. Therefore technically speaking Britain, Germany and Norway do “owe” the IMF money on a yearly basis but Germany’s payment this year is less than 1 million euros.

It’s one thing to have trade debt and other forms of “normal” government external debt but it’s quite another thing to be in debt to the IMF and the World Bank.

I think just about “everyone” knows that Romania owes quite a lot of money to these two institutions but how much? It turns out that it is exceedingly difficult to get exact numbers on this, for a variety of reasons.

An “international” bank

The IMF was created after World War 2 and early on truly functioned as a kind of international bank. Wealthy nations put money into the IMF, which was then lent out to poorer nations, who would then (theoretically) use it to invest in their economy and thus become wealthier and be able to pay back the loan.

By custom, the president (called the “managing director”) has always been a European. Right now it’s Christine Lagarde, who is French, as was her predecessor, Dominique Strauss-Kahn. Since the IMF’s inception in 1946 there have been 1 Belgian, 2 Swedish, 1 Dutch, 1 German and 5 French presidents.

That being said, the “stockholders” in the IMF are a different story. The United States controls 17.69% of the IMF, Japan 6.56%, Germany 6.12%, France and the UK each 4.51% and the other 184 member countries far smaller percentages. All decisions by the IMF are made by vote, with each country getting a vote corresponding to the percentage of the “stock” of the IMF it owns.

Therefore it’s quite clear that the United States, along with Japan, Germany, France and the UK effectively control the IMF, with the United States having the largest amount of influence. It also helps (the United States’ position) that the IMF’s headquarters are in Washington, D.C.

The World Bank, conversely, also has its headquarters in Washington, D.C. and all of its presidents since its inception in 1944 have been Americans.

Just as with the IMF, each member state of the World Bank gets votes based on the percentage of “stock” it owns, with the United States controlling 15.85%, Japan 6.84%, China 4.42%, Germany 4% and Britain and France with 3.75% apiece. With the notable exception of China, you can see that the controlling powers of the World Bank are almost identical to that of the IMF.

While both banks are certainly international in the sense that they have a global membership, both are headquartered in Washington, D.C. and are controlled by a consortium of the United States, Japan and three European nations (UK, France and Germany).

Despite this, these two banks are not identical by any means. The IMF tends to loan cash (for “general purposes”) and be heavily focused on telling debtor nations how to manage their government while the World Bank tends to specialize in funding specific projects (such as building roads or railways).

In effect, these two banks are therefore involved in far more than just loaning money. The World Bank, by authorizing (or refusing to authorize) funds for specific projects is directing individual countries on how to develop their economy. If the World Bank offers to lend a billion dollars to build a hydroelectric dam, it’s rather hard to turn them down even if later on there are severe environmental problems because of this.

The IMF meanwhile has a regular practice of physically traveling to the debtor country and telling it precisely what to do via the process of “setting targets”. The IMF will therefore tell a country that its budget deficit must be “less than 3%” and then proceed to tell it exactly how to accomplish that (slash public workers’ salaries, for instance).

Here in Romania, nearly every aspect of the national government, from its healthcare system to the continuing (but failing) efforts to sell off state-owned businesses (such as CFR Marfa) is the direct result of dictates from the IMF and World Bank (and to a lesser extent, the European Union).

Without the slightest amount of exaggeration, it is fair to say that these two banks are the “hidden” government that runs this country because without the cash that they provide and the stability that their involvement produces (such as buyers’ confidence in Romanian sovereign bonds) the common belief is that this country would instantly descend into an economic meltdown.

The man in the middle

It’s easy enough to say the IMF lent Romania a few billion euros. But where exactly do these euros go? It’s not like they drop off a bag of cash at Victor Ponta’s house. And how exactly do these loans get paid back?

And now at last we’re back to Mugur Isarescu. All of the loans, whether in the form of selling government bonds or money from the IMF, first go through the central bank (BNR). Every cent that the government takes in (from taxes, fees, etc) or is loaned (from the IMF, etc) and every cent that is paid out (in salaries or to pay back the IMF, etc) goes through the central bank.

Furthermore, even all the private enterprise that is transacted in this country, which seemingly never involves the government, is demarcated in the local currency (lei), all of which is just fiat money issued by BNR (as is also the case with dollars, euros and Japanese yen, etc).

If you’ve ever been to a big train station like Bucharest’s Gara de Nord then the BNR is like the back office running the switchboard, tasked with making sure all the trains coming in and out of the station are on time and don’t collide. And Mugur Isarescu, as the chief of BNR, is the stationmaster.

It’s also his personal job to make sure Romania pays back its loans to the IMF and World Bank. Specifically relating to the IMF, he is the one who personally writes letters to the IMF and outlines exactly how Romania is going to follow the IMF’s directives and which programs and salaries Romania is going to cut and by how much.

While technically politicians write the laws and are responsible for making decisions, they rotate in and out of office too often to be fully invested in such tediously difficult and often incomprehensible subjects as bridging loans and what a deposit guarantee fund is and how to develop and understand monetary policy.

It’s therefore with great relief that they hand over responsibility for this to the one man who understands these things and is the trusted partner of the international banks, Mugur Isarescu.

Lesser-known secrets

Based on all of this, I decided that some in-depth research into exactly who Mugur Isarescu is (and was) was warranted. As stated, some of his “secrets”, such as his membership in the Trilateral Commission, are well-known. But what else is out there?

A brief CV of Isarescu’s career

Born on August 1, 1949 as Constantin Mugur Isarescu (his full legal name) in the tiny city of Dragalasani (current population: 17,871) in southeast Valcea (county/judet).

Graduated from the local high school in 1967.

From 1967-1971 he studied at the Academy of Economic Studies (ASE) in Bucharest, obtaining his degree.

In 1975 he married Dina Elena, whom he has known since childhood, and together they have two children.

From 1971-1990 he was employed at the “Institute of World Economy” in Bucharest as a researcher and scholar.

From 1975-1980 he was simultaneously employed as a teaching assistant at ASE

From 1980-1989 he was simultaneously a lecturer on economic issues at both the “Popular University” in Bucharest and A.I. Cuza Iniversity in Iasi.

From September 1990-December 1999 he was the chief of the central bank of Romania (BNR).

From December 1999-December 2000 he was the prime minister of Romania.

From December 2000-present he has been the chief of the central bank of Romania (BNR).

Since 1994 he has also been an associate professor at a number of Romanian universities.

In 2004 he was awarded a master’s degree at Harvard University (USA).

Honors, Awards and Publications

Far too numerous to count, including presidential medals, authoring over 30 scholarly papers and several honorary doctorates at just about every major Romanian university.

Current memberships

As chief of the central bank, Isarescu holds a number of titles and memberships simultaneously.

– Member of the IMF’s board of governors

– Member of the World Bank’s board of governors

– Member of the EBRD (European Bank of Reconstruction and Development) board of governors

– Representative of Romania at the BIS

– Member of the committee for the United Nations Development Programme (Europe region)

The last three (EBRD, UNDP and BIS) are three other international banks (of differing kinds), two of which (EBRD and UNDP) have loaned money to Romania but I cannot find hard data anywhere listing exactly how much was loaned and how much Romania has yet to pay back.

The BIS is a little different in that it lends money only to central banks for the central banks themselves and these transactions are incredibly opaque.

Nonetheless, you can see that Isarescu is not just in charge of domestic monetary management (via BNR) but is also Romania’s representative to every international bank that exists.

Isarescu is also a member of, or on the board of, several other organizations including the Romanian Economics Society (SOREC) and the Romanian Numismatic (coin collecting) Society.

All in all, it’s quite clear to see that he studied economics and finance at the university (graduating in 1971), worked in academia until the revolution, and has since emerged to become this country’s pre-eminent expert on fiscal policy and economics.

It certainly makes sense that he’s been entrusted to run BNR and represent Romania in its dealings with international banks and financial institutions. Or does it?

Hiding a tree in a forest

A casual examination of both the Romanian and English versions of Mugur Isarescu’s Wikipedia page might not alert a reader to the fact that there is a lot of key information missing. For example, it lists the fact that “after the 1989 revolution, he worked for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, then for the Romanian Embassy in the United States” without going into details.

What actually happened is that in March 1990, just three months after the revolution, he was quickly dispatched to the Romanian Embassy in Washington, D.C. as the “trade representative”. Considering his expertise in the economy and foreign trade, this ostensibly makes sense. However, his tenure there was incredibly short, just three months.

He then returned to Bucharest and became the head of BNR and has never done any work since for the Foreign Ministry in any capacity. The first democratic elections were held in Romania in May 1990 so why did the government need to send a university scholar to Washington, D.C. for that specific period of time, starting just before the elections and ending right afterwards?

Unfortunately, as with all shadowy secrets, there is no way to know. Even Wikileaks, with its treasure trove of previously classified documents, does not cover this period of time. That being said, we do have the Kissinger cables, which cover a period of time from 1973-1976 and Mugur Isarescu appears in them several times.

For example, we know from this brief cable that Mugur Isarescu arrived in the United States on October 7, 1976 to participate in something called the “Multi-Regional Project on American Economy”. Considering that Isarescu had only completed his undergraduate degree five years earlier, it’s quite impressive that he was both invited to attend and given permission to do so by the Ceausescu regime.

Furthermore, two separate American officials judged that Isarescu’s English-speaking skills were adequate at a time when few Romanians were learning English in school. That being said, the cables state that Isarescu was already (in 1976) “specializing” in the United States and Canada.

It’s completely unknown what this American “project” in 1976 was about because there are literally no records on it anywhere except for those previously-classified cables. What is known, however, is that several economic and financial researchers from all around the Communist world (including in the Soviet Union) were gathered in Washington, D.C. in 1976 to participate in it.

We also get this mysterious passage from the cables:

Inasmuch as first week’s program in Washington is an extremely important part of this project, programming agency has offered to schedule special activities relating to Isarescu’s interests in New York and Washington during period October 8 to 12 so that his arrival on October 7 several days in advance of the regular project activities would also be of professional and personal value to him.

Again, no idea what these “special activities” might’ve been, but another cable states:

He [Isarescu] would like to visit IMF, World Bank, Department of the Interior, U.S. Bureau of Mines, Commodity Research Unit and Chase Manhattan Bank in New York.

Assuming he actually completed this whirlwind tour, it shows that Isarescu has been dealing with the IMF for nearly 40 years.

And although it is no longer on the IMF’s website, we know that Ceausescu first began borrowing money from the IMF starting in 1975, just a year before the 26-year-old researcher Mugur Isarescu flew to America to get a special visit with them.

During those years, a western banking institution “wooing” a Communist leader to borrow money was of unbelievable strategic importance. Furthermore, Ceausescu knew just how important those IMF loans were too because they represented a gamble that his country could thrive economically without help from the Soviet Union.

While so far we don’t have any hard proof of anything particularly “secret” going on, it is undeniable that the dictator Ceausescu authorized this young, English-speaking expert on financial affairs to travel to Washington, D.C. and meet with the very institution that was funding Ceausescu’s ambitious industrial building projects. Furthermore, aside from the cables themselves, there’s not a single public mention anywhere (at least that I can find) that Isarescu made this trip.

And there was also one other very special person that Isarescu managed to meet while he was in the United States in 1976, a man named Milton Rosenthal.

Red Horizons

During the Cold War, all Communist nations faced a dilemma. On one hand, they wanted to control their population’s exposure to the “plague” of capitalist culture while at the same time needing to have a few people travel abroad and interact with those “bourgeoisie” foreigners.

The usual solution to this was to use the intelligence agencies to employ anyone given the select permission to travel abroad and interact with foreigners. In Romania the secret police intelligence agency was known as the Securitate, roughly equivalent to the KGB in the Soviet Union.

Many countless millions of ordinary Romanians were employed by the Securitate as informants but only a few people were hired on directly as undercover agents and spies. And one of the Securitate’s favorite place to recruit new agents was the Bucharest university’s Academy of Economic Studies (AES), particularly their Foreign Commerce faculty, the very same program that Mugur Isarescu graduated from in 1971.

Dan Voiculescu, the high-profile politician, member of the (current) ruling USL coalition in parliament and owner of the “Antena Grup” media conglomerate (which controls at least five television stations and two newspapers) is well-known in Romania for having been a Securitate informant with the code name “Felix”.

Fewer people, however, know that he was a fellow graduate of the ASE in 1969. Voiculescu then went on to create an export firm named Vitrocim (which traded with capitalist countries) and it is widely believed none of that would have been possible without tacit support from the Securitate. In fact, one of his former classmates, Petre Boldisor, has stated that Voiculescu, born to a relatively poor family, obtained the money to start his firm directly from the Securitate.

Another graduate (1973) of the ASE was Misu Negritoiu. Like Voiculescu, he too worked for an import-export firm, although in Negritoiu’s case he worked directly for the government (Ministry of Foreign Trade). As soon as Mugur Isarescu returned to Bucharest in 1990, it was Negritoiu who replaced him at the embassy in Washington, D.C. In 1997 Negritoiu retired from the government to become the head of ING Bank in Romania, the position he still holds.

Another graduate of the ASE was Ioan Niculae, who after the revolution became one of Romania’s richest men, buying and selling agricultural land. Likewise, Voiculescu’s main business ventures since the revolution have all been related to agricultural land and farm products. Also much like Voiculescu, Niculae has been the subject of a number of criminal investigations.

Another graduate (1967) of the ASE is Napoleon Pop, who was allowed to travel to the United States in 1976 to study at Tufts University. Later, much like Negritoiu, he worked for the government’s Ministry of Foreign Trade until the revolution. He then began a political career and later was a member of BNR’s board of governors. In 2007 he was given an award by President Traian Basescu for his work to help create “the most spectacular period of economic growth since World War 2” in the Romanian economy.

Yet another graduate (1961) was Adrian Vasilescu. Born in 1936, he had a long career as a journalist during the Communist era and never worked in finance or banking. Then mysteriously after the revolution (in 1996, when he was then 60 years old) he became the “communications strategy coordinator” of BNR and then in 2000 the chief deputy of BNR, working directly for Mugur Isarescu, a position he still holds.

Another graduate (1970) of the ASE was Emilian Traian Andreescu, who has admitted in the press that he was employed as a spy for the Securitate, working as a “guide and polyglot” during his days as a university student. He was later sent to the United Nations headquarters in New York to spy for the government.

While very few Securitate agents have been officially confirmed, there are plenty of accusations that have been made against other ASE graduates of having been agents or spies for the Securitate, including Vasile Avram (former head of the Romanian association of football referees) and Mircea Sandu (former head of the Romanian football association). As I wrote in An Unclean Spirit, Romania has never successfully passed a lustration law and so there’s never been any public confirmation about exactly who truly was or was not a Securitate agent.

But why was the Securitate targeting the ASE in particular? A former high-ranking Securitate official explained it this way in an interview in 2011 (my translation):

We lieutenants were just simple country boys and we were given a task that was too big for us. We were trying to coordinate everything [a foreign intelligence unit] and yet we’d never been trained on how to do that. We learned what to do by reading the files, do you get what I’m saying?

We did a kind of on-the-job training and we started to get the hang of it because we were smart and able to adapt. From reading through the files, we saw how others had made all kinds of foolish and stupid mistakes before us. The school [the Securitate was running] in Baneasa was stuffed full of officers who had all kinds of military training and were from a good social background and were smart guys but they had no idea how to work abroad.

Therefore we had no other choice but to turn to the Faculty of Foreign Commerce [ASE]. Wow, those guys were ready to rock and roll down there. That’s why we [the Securitate] had so many officers involved in foreign trade. It was really the only logical solution.

Furthermore, it is now known that the “World Economy Institute” (where Isarescu worked from 1971-1990) was started by Gheorghe Marcu in 1967 when Marcu was a high-ranking Securitate general in the foreign (overseas) branch of the agency.

Likewise, Dan Ioan Popescu, who was the last Communist minister in charge of the Ministry of Foreign Trade likewise admitted that his ministry was controlled by the Securitate and that “nothing” went through there without approval by the Securitate.

The traitor who maybe wasn’t

In July of 1978 the United States scored a propaganda coup when Ion Mihai Pacepa, a high-ranking Securitate general, defected to America while he was stationed in (then West) Germany. Ceausescu responded by putting a $2 million bounty on his head but he was never assassinated and is still alive and well in the United States.

Numerous conspiracy theories abound concerning Pacepa and the man himself has given several public interviews, some seemingly very credible and others rather ludicrous, such as the claim in 2003 that he had hard proof that the GRU (Russian successor to the KGB) helped Saddam Hussein hide his Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD) that no trace of was ever found.

He also wrote a book called “Red Horizons”, detailing his (alleged) activities as a Securitate officer. However accurate or inaccurate his memoirs may be, he discusses returning home with Ceausescu and other high-ranking Communist officials from their official state visit to the United States in 1978 (Chapter 22):

“Everything Rosenthal said was even better than we had expected,” said [Foreign Minister Stefan] Andrei, referring to the discussion he had had with Milton Rosenthal, the president of the American-Romanian Economic Council at the dinner earlier that day.

“I truly was getting misty-eyed, especially when he said that the Romanian people, who are known for their intelligence and inventiveness, had managed on their own to produce goods of such high quality,” added Avram [Bunaciu] in his usual uninspiring way.

The “dinner” that Pacepa is referring to was a very fancy gala reception held for the Ceausescus (and their entourage) at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel in New York. Later in the book Pacepa describes how Frieda Rosenthal, Milton’s wife, took Elena Ceausescu on a trip to the Metropolitan Museum of Art which she (Elena) seemingly found quite boring but useful for propaganda purposes in the press back home.

In 1986, Milton Rosenthal, still head of the American-Romanian Economic Council, flew to Bucharest and was officially received by Ceausescu, partly to discuss the Most Favored Nation (MFN) status of Romania. It had first been awarded in 1975 but by the early 1980s several members of the (American) Congress were posed to remove Romania’s MFN status because of increasing concern over Ceausescu’s mistreatment of his citizens.

Therefore it’s clear that the American-Romanian Economic Council, headed by Milton Rosenthal, was, at least in part, an unofficial channel between the United States and Romania on the subject of trade. The Rosenthals were incredibly wealthy people but they were born in the United States and seemingly had no natural connection with Romania other than the fact that they owned a large manufacturing and mining corporation which potentially would’ve benefited from closer economic ties between the two countries.

All we know for sure is that the same Milton Rosenthal who was busy flattering the Romanian Foreign Minister in 1978 and Nicolae Ceausescu in 1986 was the same specific individual that Muguar Isarescu had requested to meet with in 1976.

The machine cranks into action

One of Ceausescu’s strangest (and certainly unintentional) legacies was that on the day he was killed he had left Romania in the unique position of having paid back all of its millions of dollars’ worth of loans to western banks.

Interestingly, in a 2013 interview, Isarescu stated that he was sent to Washington D.C. for those three months in 1990 because the “government” (unknown who he is referring to) believed that “some time soon” they would have to begin borrowing again from the IMF.

And indeed, after the 1989 Revolution, Romania (via Isarescu at BNR) has borrowed heavily from international financing institutions and is currently deeply in debt. But exactly how much does Romania owe?

I can’t find any hard data whatsoever on any monies that Romania owes the EBRD, UNDP (who have, in the past, considered sponsorship of the Rosia Montana goldmine) or BIS. Data from the IMF is written in a confusing format, all totals listed in SDRs, which aren’t a real currency but which get converted to a real currency (usually U.S. dollars) when the loans are paid (called “disbursed”) or repaid. The World Bank’s website is clumsy to navigate and has a surfeit of data difficult to distill into a manageable size and their figures are all listed in U.S. dollars, which makes everything doubly difficult because of course Romania’s currency is the leu and the exchange rates between all these currencies (including the SDR) fluctuates on a daily basis.

That being said, based on everything I can find and using today’s exchange rates, the sum total of post-Revolution borrowing from the IMF and World Bank amounts to slightly over 26 billion U.S. dollars. Of that sum, approximately 16 billion has been paid back (including interest and other fees) leaving Romania with an outstanding balance of about 10.5 billion dollars.

That sounds like a lot but it must be remembered that the IMF (the only source I could find) states that Romania’s total external debt “position” is 134 billion dollars so “only” about 10% of that is owed to those two international banks.

Nonetheless, according to the Romanian Ministry of Finance, the country’s GDP in 2013 was just over 442 billion lei or about 134 billion US dollars, roughly equivalent to its entire debt. Obviously that debt isn’t scheduled to be paid back in a single year but you can easily see that roughly half of all the money produced in the Romanian economy is owed to a foreign creditor. Or put another way, if Romania had zero debt then everyone’s salary would be double what it is today.

Whether the Romanian economy would be in worse shape without having taken on these loans or whether this country would be much wealthier without them is subject to debate.

What is clear, however, is that there is nearly universal acclaim and respect accorded to Mugur Isarescu for his handling of the post-Revolution economy. His image in the public eye borders on sainthood, and he regularly comes in first in opinion polls as the person that the public trusts most.

But why?

An old dog performing old tricks

Adrian Vasilecu, a former graduate of the ASE, spent 40 years working for the Communist press, churning out propaganda and glowing reports about the “beloved leader” of the nation, helping Ceausescu maintain an iron grip on the country for over 20 years as his lackeys in the media built up a cult of personality around him.

As mentioned above, Isarescu reached out to this veteran propagandist in 1996 and hired him on as the BNR’s chief of “communications strategy” despite the fact that Vasilescu had zero experience in banking or finance. According to Vasilescu, he only met Mugur Isarescu in 1990 but was hired anyway solely on the basis of his long career in Communist journalism.

And thus it came to no one’s surprise when in 2010 Vasilescu revealed that he had been hired by BNR to spend “billions of [old] lei” (millions of dollars) to buy favorable coverage of BNR in the press.

Originally it was a journalist named Tiberiu Lovin who broke the story that BNR had been spending exorbitant sums in order to have journalists report favorably on the BNR’s actions. The elderly Vasilescu, when asked about Lovin’s article, said (my translation):

I’m sorry to say this but his article is totally false because as soon as the [economic] crisis hit, we couldn’t afford to do that anymore. But yes it’s true that up until 2008 we had partnership contracts with all the newspapers and we gave them billions of old lei to encourage the newspapers to properly educate their readers about the financial and banking system.

Furthermore, Vasilescu describes how it was the IMF which encouraged this:

Everything started during the debate we had in Sofia [Bulgaria]. Representatives of the IMF came to us with the idea that newspapers shouldn’t be just commercial ventures [instead of propaganda organs for the state] but also sources of information for the public to get an education on financial and banking issues.

Thus from 1996 until 2008, BNR had those kind of partnership contracts with newspapers, magazines and any other publications dealing with finance. But in 2008 it came to an end.

As anyone who has ever studied Operation Mockingbird can tell you, when you spend tens of millions of dollars on getting the press to write articles in your favor, you can absolutely change the public’s perception of your activities.

But despite Vasilescu’s public confession that the BNR spent vast sums to gain favorable portrayals in the media, no one in Romania today knows which journalists had been bought off and which articles and TV news reports were artificially slanted in Isarescu’s and BNR’s favor.

Today most people “just know” that they trust Isarescu and yet have no hard facts to back up why they feel that way.

Friends in high places

An American “historian” by the name of Larry Watts wrote a book in 2010 called “With Friends Like These” about the history of Romania’s relations with the Soviet Union during the Cold War. According to his own website, he was an “advisor” to Romania’s Ministry of Defense from 1991-2004 and has spent considerable time in this country, including teaching classes to the SRI (Romania’s equivalent to the CIA).

He speaks Romanian (albeit with a strong American accent) and has numerous influential friends in this country, including Ion Talpes, who wrote the introduction to the Romanian-language edition of Watts’ book. Talpes, a former Communist general, is suspected to have been (PDF) one of the people who allowed the CIA to use a Romanian government building to torture people in 2003.

Watts’ book was lapped up by many Romanians precisely because it painted Romania as a brave and courageously independent nation that was constantly being victimized by the Soviet Union. When Watts held his book launch in Romania, some very important people attended. Besides his good friend Ioan Talpes, another Communist stalwart was there that evening: Iulian Vlad.

Vlad had the distinction of being the last head (1987-1989) of the Securitate before the revolution and was thus in charge of all of the secret detentions, imprisonments and executions that the secret police committed in Ceausescu’s final two years. After the revolution, Iulian Vlad was one of the few people who was arrested and tried on charges related to the old regime. Originally he was given a 25 year sentence for a wide variety of crimes but was set free by President Iliescu (Ion Talpes’ long-time boss) after serving just four years.

Since then, Vlad has been working for the Romanian-Chinese Chamber of Commerce, where he works to help promote further trade ties between the two countries. His work has been valuable enough that the Chinese government gave him an official award in 2013 for his work in “developing bilateral relations between China and Romania”.

And last but not least among the attendees at Watts’ book launch was Mugur Isarescu, who was the official host of the event as it occurred in the “Mitita Constantinescu” auditorium inside the BNR’s headquarters in Bucharest.

Isarescu wasn’t just present at the book launch but spoke to the crowd, warmly praising Watts’ book. Following Isarescu was Talpes, who lyrically praised the book as well as Iulian Vlad, and apparently everyone in attendance agreed that Watts’ book was wonderful and excellent in every possible manner despite the fact that it was poorly researched and tended to vastly inflate Romania’s “threat” to the Soviet Union’s strategy for economic and political control of Europe during the Cold War.

Check and Mate

In doing all this research, I found all kinds of interesting tidbits about Isarescu’s life and personality, including the fact that he’s watched the “Jungle Book” dozens of times and occasionally dances around at home to the famous song that the bear sings, which is his favorite tune.

I also discovered that he makes a salary of 120000 euros a year, which means he is only slightly less well compensated than the head of the Federal Reserve (America’s central bank).

And last but not least, amongst his many titles, awards, honorary degrees, memberships in banking and other financial organizations, presidential medals and honorary titles, I found one curious but unsurprising little fact.

For several years after the revolution, Mugur Isarescu served as president of the Romanian Chess Federation and is known to be an avid player of the game.

AND NOW YOU KNOW!

23 thoughts on “The Grandmaster”